Date of the last update: 10.03.2022

Broadleaf plantain is a common plant – an easily available and useful one. It is advisable to use scissors to forage it, as its fibrous leaf nerves make harvesting difficult. Owing to plantain’s distinctive features it difficult to confuse with other plants.

Table of Contents:

- Description of the plant

- Habitat

- Edible parts

- Importance in popular culture

- Use in the kitchen

- Recipe for oxidised plantain infusion

You can read this article in 4 minutes.

Description of the plant

There are several plantain species. In addition to the common (Broadleaf) plantain, those best known and most commonly used for consumption and medicinal purposes include Narrowleaf plantain (Plantago lanceolata), the hoary plantain (Plantago media), the sand plantain (Plantago afra) and the psyllium plantain (Plantago ovata).

“The white man’s foot” – this is how Native Americans called plantain when it was brought to their continent from Europe. Plantain seeds have the property that they release mucilage when moistened and stick to people’s shoes and animals’ hooves and paws. (Szymanderska, 2001, p. 30). It can also be called the “queen of roadsides”, because it is most easily found on trodden spots, in pavement cracks and wherever the ground is heavily compacted.

The oldest herbariums in the world mention plantain as an all-important useful plant. It is used both as a herb and in cooking, while its beneficial properties to the skin make it useful on hikes and camping trips. Rubbed leaves can be applied to the skin after insect bites, cuts, on bruises and swellings. There are also other ways to use plantain. With its big leaves and soothing properties, plantain was used to pad footwear to prevent foot sores and fatigue (Szary, 2015, p. 76). It is worth keeping it in mind on long hikes along trails, where you can find this synanthropic plant.

Plantain is a perennial rosette-forming herb with a short vertical rhizome. The taproot dies off early and is replaced by a bundle of adventitious roots. Leaves are set in a rosette on winged petioles, are hairless or sparsely short haired. The leaf blade is broad and oval, with 5-9 arched veins, and has entire or wavy and double-serrate edges. Flower stems are upright, slightly longer than the leaves, stiff, erect, rounded, smooth or finely furrowed, short haired. The flowers are small, greenish-brown with purple stamens, produced in a dense spike 10-20 cm long on top of the stem, 4 bent back lobes with brown midribs and long white stamens. The fruit is an egg-shaped bag. There are 4-12 Seeds in the bag (Sudnik-Wójcicka, 2011, p. 136).

Habitat

A very common species growing in the temperate zone, on both clay and humus soils in lowlands and mountains. In Poland it can be found on roadsides, pastures, water banks, in ditches and on meadows.

Edible parts

- Young leaves

- Ripe seeds

Active substances and medicinal effects

- Iridoid glycosides (aucubin, catalpol)

- Flavonoids (flavone derivatives)

- Mucilaginous compounds

- Phenolic acids

- Tannins

- Triterpene compounds (oleanolic acid derivatives)

- Vitamin C and K

- Mineral compounds, especially potassium

Extracts from the leaf are used as a shielding (mucilaginous compounds) and anti-inflammatory (iridoids, tannins) medicine in gastrointestinal diseases, bronchitis and throat inflammations. (Strzelecka and Kowalski, 2000, p. 44).

Importance in popular culture

Leaves of different plantain species have been eaten all over the world (in Europe, China, North America). Although not commonly used in Polish rural cuisine, they were, however, popular in Belarus, where they were eaten in spring.

Letters written in response to Rostafiński’s proclamation from the territory of present-day Belarus report on eating some kind of plantain. Słotwińska wrote about Ravonichi village (former Igumen district): “With the coming of spring, country people first start foraging sprouting nettle and schnitka (i.e. ground elder – note Ł. Łuczaj) for food, then sorrel, hogweed and plantain (Plantago), which they call ‘Tryputnik’.” (Łuczaj, Dziko rosnące rośliny jadalne użytkowane w Polsce od połowie XIX wieku do czasów współczesnych, 2011, p. 102).

Plantain is mentioned in a Chinese herbarium from the 1st century AD. It was also used in the Middle Ages. Shakespeare mentions it as a remedy for skin injuries. According to folk beliefs in old France and Bosnia, common plantain herb was a medicine for men, while narrow leaf plantain was for women. (Strzelecka and Kowalski, 2000, p. 44)

Use in the kitchen

Many authors describe the taste of plantain as intense and bitter. One author compares the taste of plantain as that of mushrooms. (Fleischhauer, Guthmann and Spiegelberger, 2014, p. 152) Szymanderska describes the taste of fresh plantain leaves as salty-sweet with bitter notes. (Szymanderska, 2001, p. 30) Sundgren, on the other hand, writes it is mild and slightly sour. (Sundgren, 2018, p. 147)

Plantain leaves can be used in various soups, sautés, as an addition to stir-fried vegetables and casseroles. (Łuczaj, Dzika kuchnia, 2013, p. 17) Young leaves can also be prepared in exactly the same way as young boiled cabbage, served in spring with fried onions and dill.

Slightly older plantain leaves collected in the summer can be used for oxidised enzyme teas. Oxidation process produces a very pleasant and delicate flavour and fragrance, with notes of honey and vanilla.

In late summer and early autumn, we also harvest the seeds. When cooked, the seeds are mucilaginous and packed with nutrients. They can be used as a valuable addition to many dishes and breads or be simply cooked as porridge. (Łuczaj, Dzika kuchnia, 2013, p. 17).

Recipe for oxidised plantain infusion

- Forage the plant.

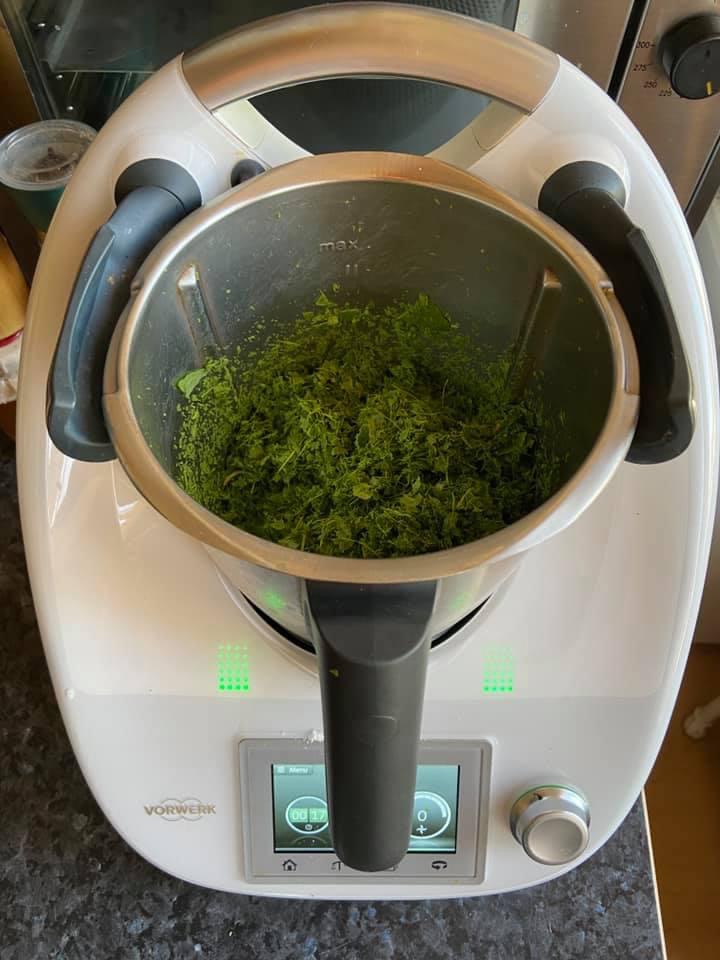

- Crush it.

- Put into jars.

- Oxidize the herb in any device that can maintain a temperature of 40-50 centigrade. Run the process for 2-3 days. On the second day you need to look into the jar every few hours, unscrew it and smell. The oxidation is completed when the smell of plantain is no longer grassy and green, but gains a pleasant fruity and honey-floral aroma. If you happen to overdo the oxidation time you will smell mould instead. In that case simply discard the herb.

- After the oxidation process, the raw plant changes its colour and is fragrant.

- Dry plantain at a temperature no higher than the one applied to oxidise the infusion, and then store it in an airtight container until the infusion develops its full fragrance, preferably several months.

Brew the dried herb as you would black tea (1 full teaspoon of infusion per cup of boiling water). Leave for a few minutes to steep.

Oxidised plantain infusion has a very pleasant, delicate aroma. It also has a very nice, slightly amber colour.

Explore more: Chaga – a magical, health-promoting mushroom in your forest

Sources:

Fleischhauer, S. G., Guthmann, J. i Spiegelberger, R. (2014). Jadalne rośliny dziko rosnące. Białystok: Vital editing house.

Kalemba-Drożdż, M. (2014). Pyszne chwasty. Bielsko-Biała: Pascal editing house.

Łuczaj, Ł. (2011). Dziko rosnące rośliny jadalne użytkowane w Polsce od połowy XIX wieku do czasów współczesnych. Etnobiologia Polska Vol.1, 57-125.

Łuczaj, Ł. (2013). Dzika kuchnia. Warsaw: Nasza Księgarnia editing house.

Mederska, M. i Mederski, P. (2015). Atlas dzikich kwiatów. Warsaw: SBM editing house.

Mowszowicz, J. (1979). Pospolite rośliny naczyniowe Polski. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

Senderski, M. E. (2017). Prawie wszystko o ziołach i ziołolecznictwie. Podkowa Leśna: Mateusz E. Senderski.

Strzelecka, H. i Kowalski, J. (2000). Encyklopedia zielarstwa i ziołolecznictwa. Warsaw: Polish Scientific Publishers PWN.

Sudnik-Wójcicka, B. (2011). Flora Polski. Rośliny synantropijne. Warsaw: Multico Editing House.

Sundgren, L. (2018). Zielnik – jedzenie i domowe kuracje z łona natury. Warsaw: Marginesy Sp. z o.o. editing house.

Szary, A. (2015). Tajemnice bieszczadzkich roślin wczoraj i dziś. Rzeszów: Carpathia editing house.

Szymanderska, H. (2001). Pokochajmy zielsko. Zapomniane zioła w naszej kuchni. Warsaw: Muza SA.